Just Earth News | @justearthnews | 01 Aug 2017

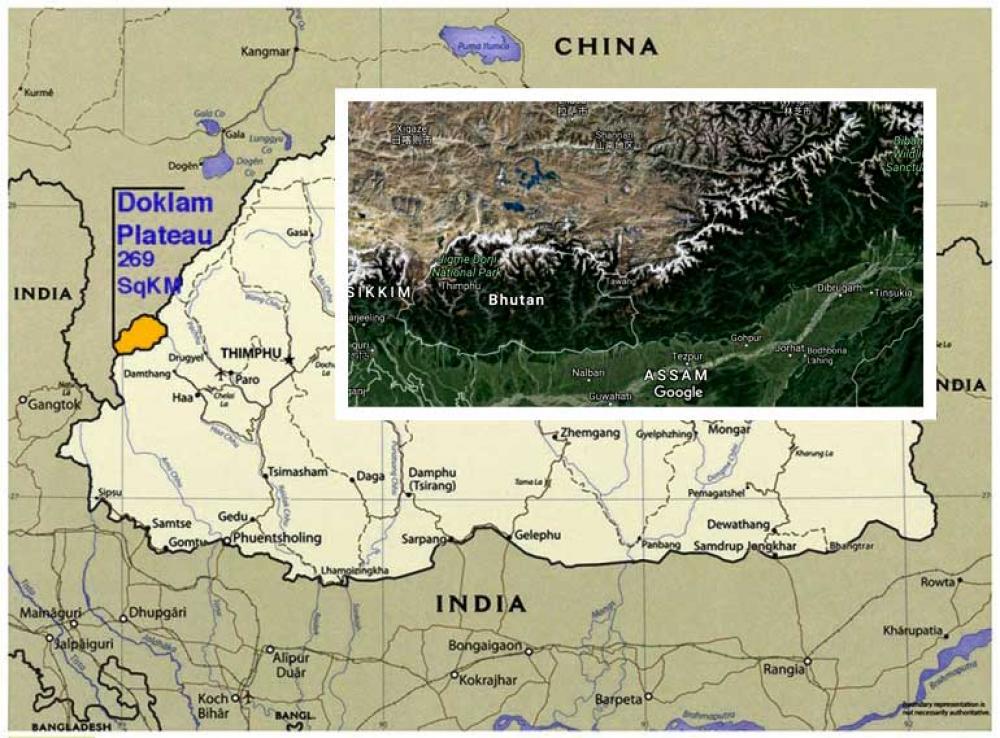

As the Doklam standoff continues between China and India, Bhutan has been caught between the two nuclear armed giant neighbours. The Himalayan territory of Doklam is actually a narrow plateau lying in the tri-junction of Bhutan, China and India. It is a triboundary point of all three nations. The disputed territory lies in Bhutan to be more specific.

China and Bhutan in 1998 had in an agreement decided to maintain peace and the status quo in the region but the trouble started with China attempting to extend a road in a sector of Doklam which threatens the border security of India. Bhutan has already issued a demarche against China though the latter continued to raise the pitch and even more recently indirectly calling India as an "invading enemy".

But what does Bhutan think about the whole issue?

Two recent articles by Bhutanese on the Doklam issue are worth analyzing. The first by Tenzing Lamsang, Editor of The Bhutanese on 1 July 2017 which makes a factual case relating to the Chinese road construction activity in Doklam area, while the second article a day later was by popular Bhutanese blogger, Wangcha Sangey, who attempted to present a ‘Bhutanese’ perspective on the issue.

This focus is necessary as there is excessive attention being paid to this matter in the Chinese and Indian media and also since the territory in question lies in Bhutan.

Tenzing Lamsang writing in The Bhutanese, on the Doklam border issue provides a chronology of events on the issue starting with the Bhutanese Foreign Ministry release of 29 June. This clearly states that construction of roads by the Chinese is in violation of the 1988 and 1998 written agreements.

This appeared in response to the Chinese construction of a road by the Chinese PLA from Doka La in the Doklam area towards the Royal Bhutanese Army camp at Zompelri on 16 June 2017. Bhutan fired its first missive on 20 June when Major General V. Namgyel, Bhutan’s Ambassador to India, issued a formal ‘demarche’ to the Chinese Embassy in New Delhi asking China to stop the road construction.

This was followed by the Indian Ministry of External Affairs issuing a press release on 30 June 2017 stating that “It is our understanding that a Royal Bhutan Army patrol attempted to dissuade them from this unilateral activity."

"The Ambassador of the Royal Government of Bhutan (RGOB) has publicly stated that it lodged a protest with the Chinese Government through their Embassy in New Delhi on 20 June.”

India's external affairs ministry release also stated that “in coordination with the RGOB, Indian personnel, who were present at the general area in Dokala, approached the Chinese construction party and urged them to desist from changing the status quo.”

The change in status quo referred to the attempt by China to move the tri-junction between India, China and Bhutan from Batang La to Gyamochen (Mount Gipmochi) which the Chinese claimed to be the starting point of the tri-junction as per the 1890 Anglo-Chinese convention.

India informed China that the two Governments had in 2012 reached an agreement on the basis of the alignment of the tri-junction boundary points between India, China and third countries and that is would be finalized in consultation with the concerned countries and that Chinese actions in Doka La violated this agreement.

It is of note that the larger area where the incident has occurred is known as Doklam by the Bhutanese. The Chinese were attempting to do some site cutting to extend a road down south from Doka La towards the RBA camp at Zompelri.

Lamsang states that the RBA first tried to dissuade the Chinese road construction team which refused to cooperate. It was only after that happened did Indian soldiers enter the area and physically halted the construction. Chinese soldiers came back some time later and destroyed a couple of small Indian military bunkers in the vicinity. It is admitted that the area through which China is trying to build a road is Bhutanese territory, which is also claimed by the Chinese and is part of the ongoing annual boundary negotiations.

The Chinese side has built a major road till the Yatung in the Chumbi valley.

When seen from a Chinese perspective, it makes perfect sense for them to have control of the Doklam plateau as this would give them a shoulder on which to protect the narrow Chumbi Valley. That is precisely why they are claiming 269 sq km of Bhutanese territory.

For Bhutan, loss of territory is not in its interest and this issue has been discussed in past sessions of the National Assembly, with both pre-democracy Chimis (representatives) and also post-democracy MPs bringing up the issue of Chinese encroachments. In the 1996 ‘package deal’ China offered to ‘give up’ its claims to 495 sq km of land in the Pasamlung and Jakarlung valleys in Bhutan’s north-central sector of Bumthang in exchange for Bhutan giving up 269 sq km in Doklam.

Lamsang summarises the history of Bhutan’s boundary negotiations with China, which began with India being a part. However, with persistent Chinese pushing India was forced to withdraw.

During discussions it was found that China refused to recognize the watershed principle as being the factor in deciding the boundaries between Bhutan and Tibet. Pertinently, from 1984 onwards, Bhutan began to bilaterally deal the issue with China.

In 1988, some broad guiding principles of the talks were agreed upon to maintain peace and not use force to change the status quo. This was further elaborated and defined in a more detailed agreement in 1998. Between 1984 and 2016 there have been 24 rounds of boundary talks. The 24th boundary meeting held in Beijing endorsed the report of the Joint Technical Field Survey of the disputed areas in the Western Sector carried out by the expert groups of both sides.

Now we come to the second article is by prominent Bhutanese blogger Wangcha Sangey and this was written in response to Lamsang’s piece in the Bhutanese.

Sangey’s angst is that Lamsang chose to expound the Indian Government positions/views upon the Bhutanese public through his article. While Sangey claims that he is in fact responding to articles in the Indian media, his target clearly is Lamsang. He makes several points of a historical nature which can be summarised as follows. It was at China’s insistence that Bhutan decided to deal directly with China. It is incorrect to say that India ‘permitted’ Bhutan to deal directly with China. Bhutan decided at that point in time that this was a step taken in its national interest. While Sangey claims that much progress has been achieved through the 24 rounds of boundary talks, it is not clear what is the give and take on the border?

Sangey blithely asserts that the Government in Bhutan is “in no position to bare all the uncomfortable truths including heavy pressures from India to demand more strategic land from China.”

One would like to know the basis of such assertions. After all, this sounds more like a Chinese statement than a Bhutanese one. Sangey claims that Bhutan was in no position to negotiate its southern border with India and that it was done quietly. In fact the process of border negotiations and demarcations was long drawn and took place between 1973 and 1984. It took several more years and it was not until December 2006 that the final strip maps were signed formally demarcating the 699 km border.

It should be noted that border demarcation was done bilaterally and not unilaterally as the British did in the case of the 1890 Anglo-Tibet Convention. Also, to merely claim that India laid down the riot act and asked the Survey of India to unilaterally lay down boundary pillars is to incorrectly state the facts. Respect for Bhutan’s territorial sovereignty lies at the heart of India’s relations with Bhutan and to claim that “Bhutan is more vulnerable to a takeover by India than by China” is a misreading of the situation.

There is no doubt about Sangey’s love for Bhutan. He couches it in true diplomatic language by playing the China card and the India card. He feels that Bhutan must realistically assess what demands it can make on China, by that he means negotiating the border agreement.

According to Sangey the best solution would be for China or India to forcefully take over the Doklam plateau. One is sure that he is aware of the fact that China’s PLA has already taken over the Doklam plateau and has military outposts there. This is an ingenious way of telling the Bhutanese that their territory is already under the control of the Chinese.

Despite several Bhutanese National Assembly debates and Resolutions on the subject, Sangey claims that Doklam has no value for Bhutan. So only China and India have a strategic interest in this area? He makes it clear that he takes the Chinese line on the 1890 Convention which identifies Mount Gipmochi as the tri-junction. And therefore, he claims that there is not much that India can do in this regard and concludes that “the Sikkim door which India possessed is closed”.

According to Indian officials, the country never pushed Bhutan to claim as much of the Doklam Plateau as it can. India claimed it has never dictated any country for its own security interests. What India is currently doing is to protect its interests at Doka La and promote the understanding that Chinese road construction past this pass upto Zompelri ridge and beyond will threaten Bhutan.

According to Indian officials, the country never pushed Bhutan to claim as much of the Doklam Plateau as it can. India claimed it has never dictated any country for its own security interests. What India is currently doing is to protect its interests at Doka La and promote the understanding that Chinese road construction past this pass upto Zompelri ridge and beyond will threaten Bhutan.

One cannot but agree with Sangey when he states that “Bhutan is placed in a near impossible position”. And it is true that China will never surrender the strategic position that it has gained at Doklam Plateau. Again, it is a distortion of facts to claim that India is insisting upon Bhutan to wrest from China larger portion of Doklam Plateau.

Sangey makes his loyalties clear when he informs the reader that while China has shown willingness to accommodate Bhutanese requests it will never do so, on the tri-junction with India and Bhutan. That is why, according to Sangey, Bhutan wants to give up Doklam to China. It is interesting to see that the writer compares India’s strategic concerns about the Siliguri corridor with China’s concerns about the Chumbi Valley and the ‘whole of Tibet’.

While one can agree that each nation has a right to see its security from their perspective, China’s assertive attitude as far as territory is concerned is lost sight of. Sangey confirms what most analysts believe when he states that “China may not wait forever for Bhutan to get Indian clearance. Chinese security concerns would outweigh any ties, including with Bhutan.”

A simple of reading of Lamsang’s article shows that he is only trying to present a balanced picture of the situation as it developed and does not in any way make light of the efforts of the RBA to defend Bhutan. The RBA is a fine institution which is trained by the Indian Army. This training gives them the capacity to defend their territory to the extent that it is humanely possible.

According to Sangey, Indian Army is in Bhutan for India’s security and not for the defence of Bhutan. Sadly this gentleman does not know his history or politics. While it may be correct that the Indian Army’s recent actions are to protect India’s interests, to generalise this to include Bhutan’s external relations misses the wood for the trees.

Lest we forget there are two treaties signed in 1949 and 2007 which provide ample evidences of the nature of Indo-Bhutan relations. Yes, there have been aberrations, but they have not reduced the linkages at all levels between the two nations. This should remain so in the near and distant future.